JUMP TO TOPIC

- Is a Parallelogram a Rectangle?

- Defining the Rectangle

- Structural Distinctions

- Properties

- Exercise

- Example 1

- Solution

- Solution

- Example 3

- Solution

- Example 4

- Solution

- Example 5

- Solution

- Example 6

- Solution

- Example 7

- Solution

- Example 8

- Solution

- Importance in Mathematics and Real-world Applications of the Parallelogram-Rectangle Distinction

- Educational Importance

- Construction and Architecture

- Engineering

- Art and Design

- Astronomy and Physics

- Geography and Cartography

Geometric shapes have intrigued mathematicians, artists, and thinkers for centuries. One particular conundrum that often arises is a parallelogram a rectangle?

This question might sound straightforward, but there’s more to it than meets the eye. In this article, we’ll explore the defining properties of both shapes and establish the relationship between them.

Is a Parallelogram a Rectangle?

Yes, a parallelogram is a rectangle if all the angles of the parallelogram are right angles. To find if a parallelogram is a rectangle, we first dive into the understanding of parallelogram and rectangle.

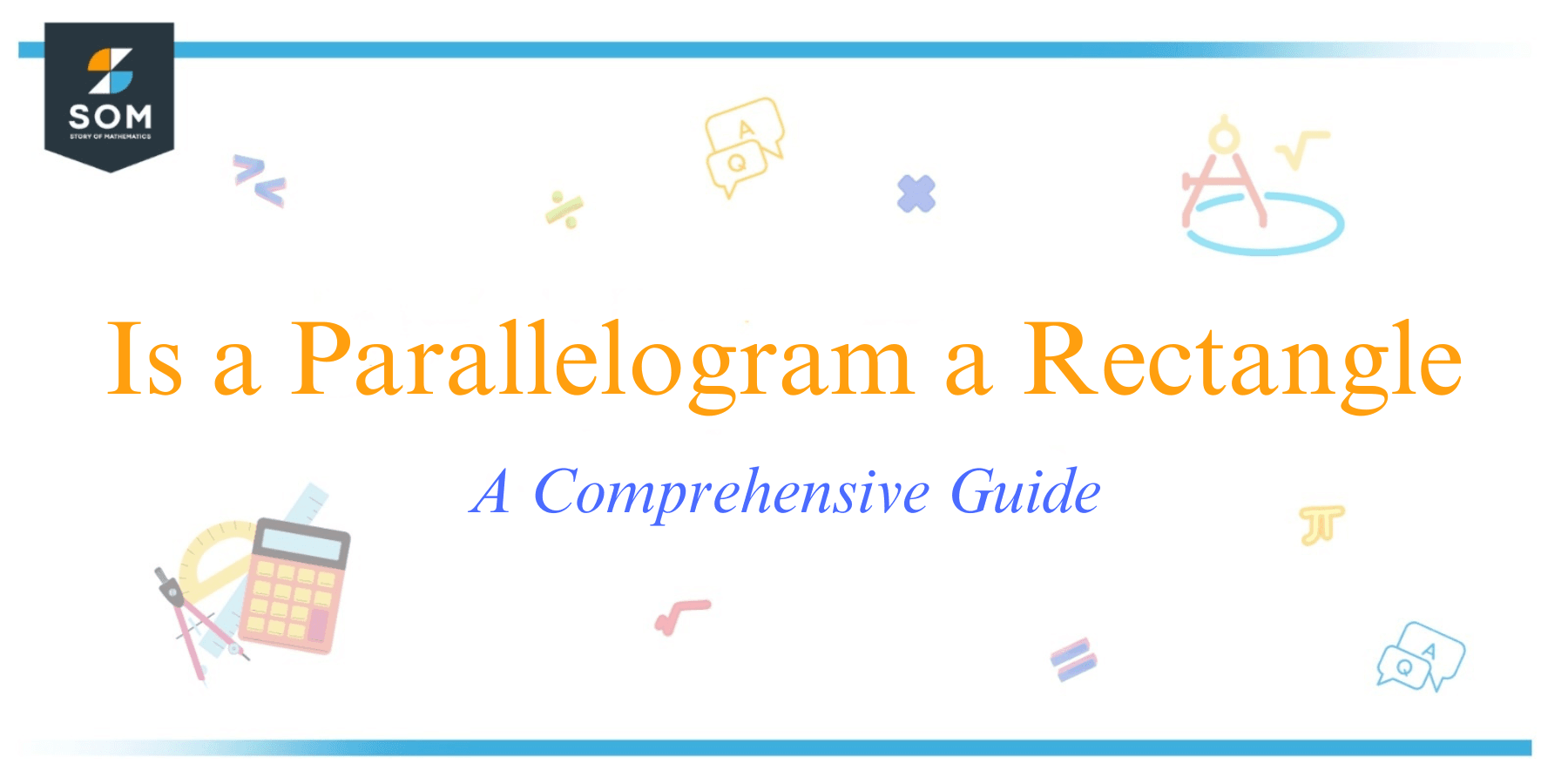

Defining the Parallelogram

To begin, let’s define a parallelogram. A parallelogram is a four-sided polygon (a quadrilateral) where opposite sides are parallel. By nature of this definition, it ensures that:

- Opposite sides are of equal length.

- Opposite angles are congruent.

- Adjacent angles are supplementary.

- Diagonals bisect each other.

It’s essential to note that parallelograms can have varied angles, and not all angles in a parallelogram are necessarily right angles. In fact, a parallelogram can be skewed in such a way that no angles are right angles.

Figure-1.

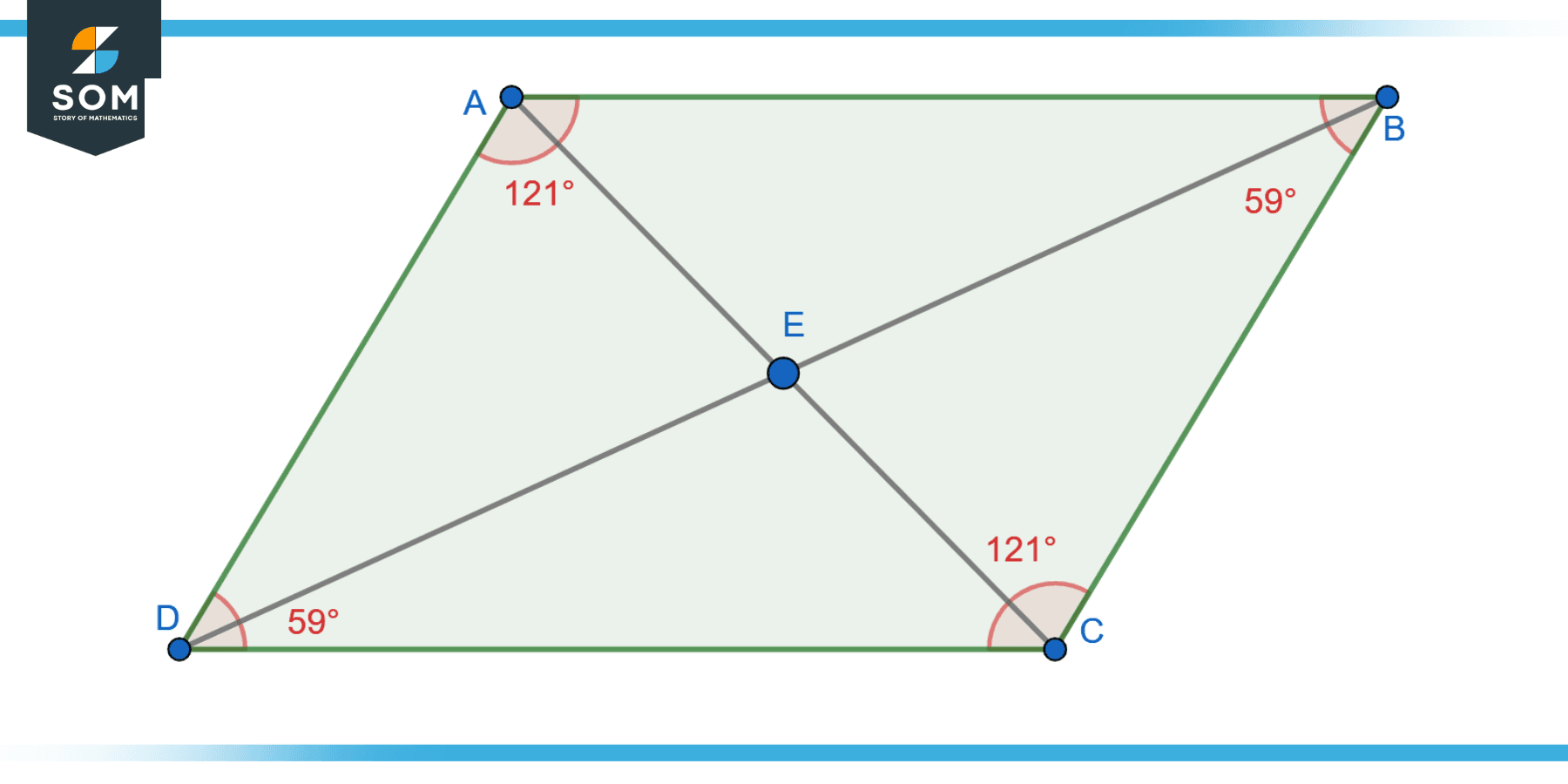

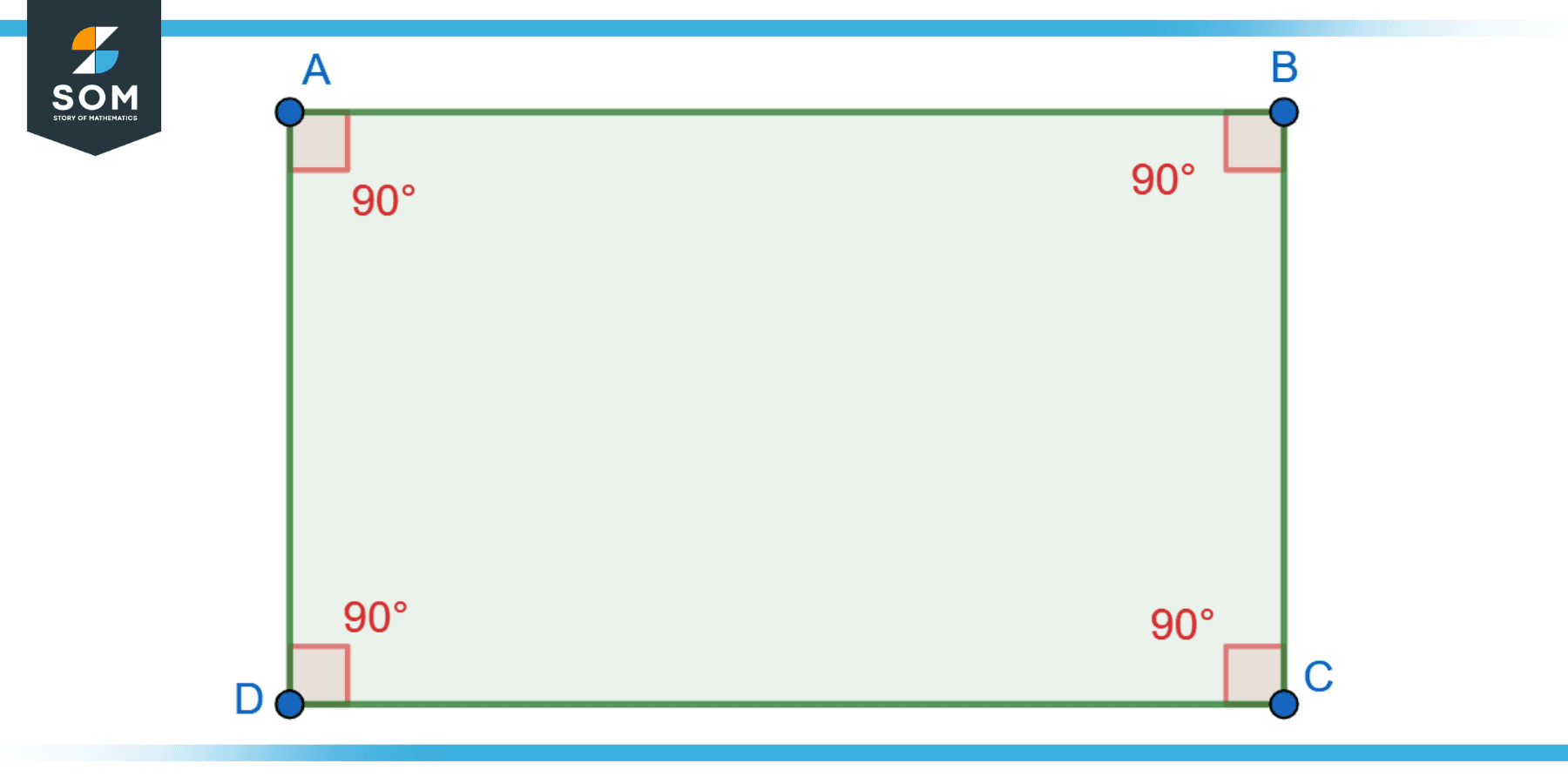

Defining the Rectangle

A rectangle is also a four-sided polygon, but it comes with its own set of specific properties. For a quadrilateral to be termed a rectangle. A parallelogram with an additional characteristic – all interior angles are right angles. This brings with it other inherent properties:

- Diagonals are congruent.

- All sides form 90-degree angles with adjacent sides.

From the above definition, one can infer that a rectangle is a specific type of parallelogram – one where all the angles are right angles.

Figure-2.

Structural Distinctions

The core difference between a generic parallelogram and a rectangle lies in the angles. A rectangle is essentially a parallelogram with all right angles. The introduction of right angles in a rectangle ensures its diagonals are not only bisected but also congruent.

On the other hand, a parallelogram’s angles can vary, and its diagonals are generally not of equal length unless it’s a rectangle.

The root of the confusion between parallelograms and rectangles often lies in our early exposure to geometric shapes. In elementary education, we are introduced to squares and rectangles before parallelograms. By the time we encounter parallelograms, our mind is already conditioned to equate four-sided figures with right angles, inadvertently associating all parallelograms with rectangles.

Moreover, the world around us is filled with more visual examples of rectangles (like doors, books, and screens) than the skewed versions of parallelograms, further cementing the misconception.

Properties

Properties of a Parallelogram

Opposite Sides are Parallel

This is the defining property of a parallelogram. The opposite sides will always run parallel to each other, ensuring they will never intersect.

Opposite Sides are Congruent

Not only are the opposite sides parallel, but they are also of equal length.

Opposite Angles are Congruent

The angles directly opposite each other in a parallelogram are always of equal measure.

Consecutive Angles are Supplementary

This means that if you take any angle in a parallelogram, the angle next to it will always add up to 180 degrees with it.

Diagonals Bisect Each Other

If you draw diagonals from opposite corners of a parallelogram, they will always intersect each other at their midpoints.

Diagonals are NOT Necessarily Congruent

This differentiates parallelograms from rectangles. In a generic parallelogram, the diagonals can be of different lengths. However, if they are congruent, then the parallelogram is a rectangle.

Properties of a Rectangle

Since a rectangle is a specific type of parallelogram, it inherits all the properties of parallelograms. However, it has additional properties of its own due to its right angles:

All Angles are Right Angles

This is the defining property of a rectangle. Each interior angle is 90 degrees.

Opposite Sides are Parallel

As with all parallelograms.

Opposite Sides are Congruent

All opposite sides are of equal length.

Diagonals are Congruent

Unlike a generic parallelogram, in a rectangle, the diagonals are always of equal length.

Diagonals Bisect Each Other

The point where the diagonals intersect divides each diagonal into two equal parts.

Diagonals are Perpendicular Bisectors of Each Other

This is exclusive to squares (which are a type of rectangle) and not to all rectangles.

Exercise

Example 1

Given a parallelogram ABCD where AB = CD = 10 units, BC = AD = 6 units, and the measure of angle A = 90 degrees. Is ABCD a rectangle?

Figure-3.

Solution

If angle A is 90 degrees, and since ABCD is a parallelogram, angle C will also be 90 degrees. Also, opposite angles in a parallelogram are equal, so angle B and angle D will both be 90 degrees. Thus, all interior angles of ABCD are 90 degrees. Hence, ABCD is a rectangle.

Example 2

Given a parallelogram EFGH with diagonal lengths EF = GH = 15 units. Is EFGH a rectangle?

Solution

Since the diagonals of EFGH are congruent, EFGH is a rectangle.

Example 3

Given a parallelogram IJKL where IK = 12 units and JL = 13 units. Is IJKL a rectangle?

Solution

The diagonals of IJKL are not congruent. Therefore, IJKL is not a rectangle.

Example 4

In parallelogram MNOP, angle M = 90 degrees, and MN = 8 units. Is MNOP a rectangle?

Solution

If angle M is 90 degrees in the parallelogram, then all the other angles will also be 90 degrees (since opposite angles in a parallelogram are equal, and consecutive angles are supplementary). Thus, MNOP is a rectangle.

Example 5

Given a parallelogram QRST with QT = 14 units and RS = 16 units. Is QRST a rectangle?

Solution

The diagonals QT and RS are not congruent. Therefore, QRST is not a rectangle.

Example 6

In parallelogram UVWX, UV = 5 units, WX = 5 units, and angle U = 90 degrees. Is UVWX a rectangle?

Solution

If angle U is 90 degrees, and UVWX is a parallelogram, then all angles in UVWX are 90 degrees. Hence, UVWX is a rectangle.

Example 7

In parallelogram ABCD, if AB is perpendicular to AD, and AD = 7 units, is ABCD a rectangle?

Solution

Since AB is perpendicular to AD, it means that angle A is 90 degrees. In a parallelogram, if one angle is 90 degrees, all angles are 90 degrees. Thus, ABCD is a rectangle.

Example 8

Given a parallelogram EFGH, if EF bisects angle E and HG bisects angle H, and EF = 9 units, is EFGH a rectangle?

Solution

The property mentioned here (diagonals bisecting angles) is true for all parallelograms, not just rectangles. Therefore, just based on this information, we cannot conclude that EFGH is a rectangle. More information about angles or side lengths would be needed.

Importance in Mathematics and Real-world Applications of the Parallelogram-Rectangle Distinction

Educational Importance

Mathematics

Understanding the difference between parallelograms and rectangles is foundational in geometry. It helps students build a robust geometric intuition, enabling them to grasp more complex concepts such as the properties of rhombuses, squares, and trapezoids.

When students recognize that not all parallelograms are rectangles, they are better prepared to solve problems that require distinguishing between different types of quadrilaterals and applying their respective properties.

Construction and Architecture

Building Designs

The choice between using a parallelogram and a rectangle shape can influence both the aesthetic and functionality of a structure. For instance, parallelogram-shaped buildings or rooms can offer unique architectural designs but might pose challenges in terms of furniture arrangement compared to rectangular spaces.

Structural Integrity

The angles in structures impact how forces are distributed. Rectangular structures, with their right angles, distribute forces differently compared to parallelogram structures. This distinction can be crucial in areas prone to external forces like earthquakes or strong winds.

Engineering

Machine Design

Components of machinery may be designed based on the properties of these geometric figures. For example, some mechanical linkages may use parallelogram structures to maintain certain angles while in motion, whereas rectangular components might be preferred for stability.

Computer Graphics

When rendering 3D objects onto 2D screens, transformations often involve matrix math that leans heavily on geometric principles. Differentiating between parallelograms and rectangles is crucial in these calculations, especially when dealing with perspective.

Art and Design

Visual Appeal

Artists often choose shapes based on the emotions they evoke. Rectangles, being more regular and stable, might evoke feelings of order and predictability. In contrast, parallelograms, with their slanted sides, can give an impression of movement, dynamism, or instability.

Functional Design

Designers, especially in fields like furniture or product design, need to consider the practical implications of shapes. A rectangular table, for instance, provides a different utility and space dynamic compared to a parallelogram-shaped one.

Astronomy and Physics

Stellar Observations

When observing distant celestial bodies, the instruments used might produce image distortions. Understanding the geometric implications can help astronomers correct these distortions, converting parallelogram shapes back to their original rectangular forms.

Optics

In the world of physics, especially optics, the way light interacts with surfaces can transform rectangular shapes into parallelograms in the observer’s view. Knowing the distinction helps in designing lenses and predicting light behaviors.

Geography and Cartography

Map Projections

Translating the Earth’s spherical surface onto flat maps often involves geometric transformations. In this process, certain areas, especially near the poles, may appear distorted. Recognizing and adjusting for these distortions is essential, and understanding the nuances between shapes like parallelograms and rectangles aids in this.

All images were created with GeoGebra.